Even before 2020 descended on us all the Royal Ballet in the UK was clocking up hundreds of thousands of views for their videos on YouTube that focused on health and fitness. This video from 2017 is the first in a series of “health and fitness tutorials for beginners inspired by classical dance”.

So it was perhaps not a huge surprise that in my recent Digital Works Podcast conversation with Sadler’s Wells’ Ankur Bahl he talked about the succes they have seen with the fitness and technique focused video content they have produced this year.

Still in the world of dance it has been interesting to see that companies like English National Ballet are launching fully-formed digital subscription programmes entirely focused around “training and workouts to enjoy at home”.

But it’s not just dance.

Examples in the wild

Elsewhere I have observed organisations seeing surprising levels of success around workshop, participatory and learning-focused activity delivered online.

Examples include Opera North’s From Couch to Chorus scheme, “a fun four-week series of workshops where you’ll learn all the best singing tips and tricks from a professional choral director from Opera North” (which has returned for a second, festive-focused term), the Globe’s Telling Tales Festival “a range of online and physical events” (the physical events have been cancelled due to lockdown but there are still 10s of virtual events to enjoy), and the Children Theatre Company’s Virtual Academy.

Outside the performing arts the V&A Learning Academy look to have been selling a lot of places for their online courses (if you look at their listings every course is currently sold out).

And something to note is that all of these examples are revenue generating.

Perceived value

Which got me thinking. It is perhaps more straightforward to move some of this sort of activity online than it is to, for example, capture/stream a fully staged performance. But what has been most interesting to me is that audiences are, demonstrably, very willing to pay for this.

Obviously the canvas of horrors that is 2020 plays a part in this. We are all stuck inside to varying degrees, kids are bored, people are wanting to keep themselves busy.

Workshops, learning a new skill, or working out are all antidotes to this.

And perhaps the perceived value, or value exchange, is more straightforward with this type of activity. Maybe it is clearer, or simpler. I learn a thing, or occupy the kids, and I’m happy to part with some money for that to happen. I am clearly getting something in return.

Value exchange for performance is more knotty and wrapped up in the expectations around what that experience has traditionally involved. Also organisations have, over the course of 2020, and for years before that, created an expectation that captured performance content should be free.

Delivering the type of education/participation work I’ve outlined above in a digital context is relatively new, so perhaps audience expectations or preconceptions around price and value haven’t yet crystalised in the same way.

Research to back this up

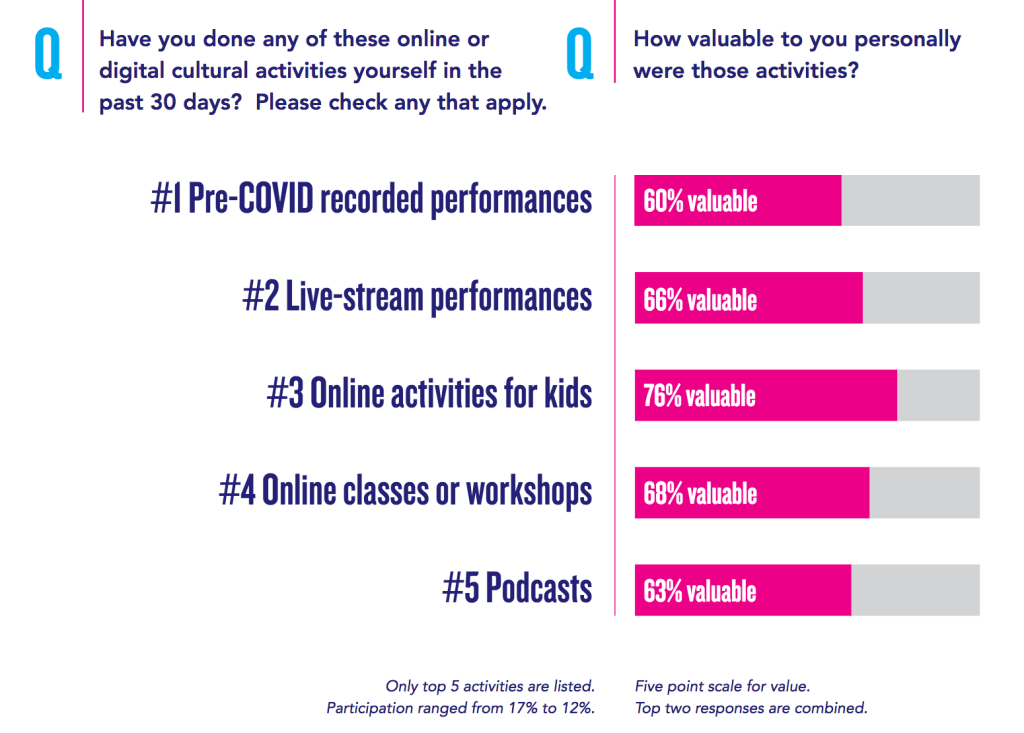

And there is some emerging research that supports this. LaPlaca Cohen’s most recent Culture Track report, “Culture + Community in a Time of Crisis“, found that learning-based activities are seen as “particularly valuable”.

This feels like an exciting and underexplored opportunity for many cultural organisations.

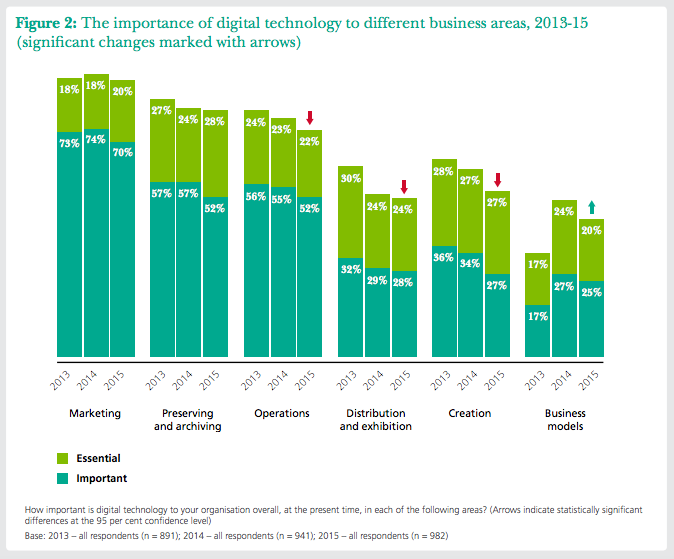

Traditionally education, participation, learning, whatever you want to call it, has not been at the front of the queue when it has come to digital priorities. Usually the rationale is that these activities have not (traditionally) been revenue generating in the same way (or to the same level) as, say, selling tickets to performances or exhibitions has.

It would appear that assumption no longer holds (as) true.

Equally I have found that colleagues working in these teams are sometimes less comfortable or confident when it comes to thinking digitally. That seems like it has started to change over recent months, I hope we see much more of it.