Conversion rates are often thrown about as a useful metric. And they are (with the usual caveats). They can provide a helpful indication about whether or not the various bits of your website are doing what they should. Or where there are issues that you need to address.

However I often have conversations with people who are beating themselves up because they are suffering with what they perceive as very low conversion rates. And I’m not sure they’re being all that fair on themselves.

The way that Google Analytics works out your conversion rate is it takes all your traffic (sessions) unless you tell it otherwise. It then takes the number of completed goals (transactions, or whatever it is you’re getting the conversion rate for) and works out your conversion rate from that.

So, for example if you had 5,000 sessions and 100 transactions then your conversion rate would be 2%. But is this number useful, or accurate? I’d argue it potentially isn’t.

If those 5,000 sessions include visitors who aren’t your target market and were never going to buy anything then they shouldn’t be included in your calculations.

As with so many of the metrics in GA, top level numbers often aren’t that helpful or meaningful.

Going back to the example above, what if half of those sessions had come from visitors from overseas who had been following a link to a blog post that cropped up on social media (an unlikely scenario but bear with me). Those visitors are unlikely to ever buy, say, a ticket for a performance so they probably shouldn’t be included in your numbers when you’re looking to calculate whether your production pages are converting traffic. Because that traffic was never going to buy a ticket and didn’t even visit the production pages.

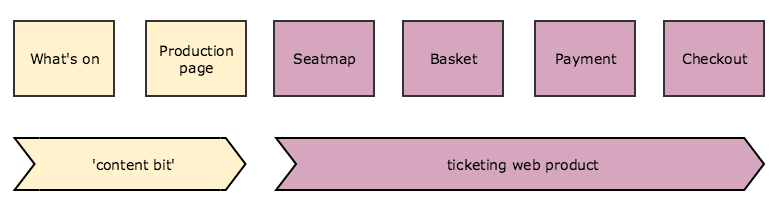

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts (such as this one on funnel analysis and this one on ‘clarity of purpose‘) each part of your digital activity should have a clear purpose, and should be measured on that basis. It’s no use judging your contact page on whether or not it’s good at selling tickets.

This means using custom segments, setting up clear goals, and utilising things like custom dimensions and events if you need to, so that you can accurately measure the effectiveness of your site.

Going back to our example scenario, if your current marketing efforts are aimed at getting people from the city you’re located in, onto your production pages, to buy a ticket, then create a segment that allows you to identify a) if that’s happening, b) to what level that’s happening and how, and c) whether or not it’s meeting the objective you’ve set to the level you need (i.e. buying a ticket). If it is, then great (and you can begin to further optimise your campaign accordingly), if it isn’t then this will at least allow you to begin to identify where the issues may be. You might be getting the right sort of traffic but it’s not converting and through isolating and being able to analyse this traffic you will be able to begin to see where and how users are being tripped up.

Don’t use ‘all traffic’ to work out conversion rates as there will inevitably be ‘irrelevant’ traffic being swept up in this. If a session is landing on the site and hitting pages that play no purpose in the user journey for the goal that you’re analysing the conversion rate for then you’re including traffic that plays no role in the scenario you’re examining. Which isn’t helpful for anyone.

Relying on top level metrics means you’re never going to be able to identify actionable insights. Your website will likely have a number of goals whether that’s newsletter signups, enquiry submissions, donations, membership purchases, account setup, ticket purchases (you get the idea).

Each of those goals should have a clear user journey, ending in the goal being achieved. By properly measuring the goals you can work out if your various user journeys are working as they should be. And whether or not you’re actually enjoying any success.

So, to summarise (as ever, I’ve gone on a bit).

- If your conversion rates are looking a bit sad, are you actually being fair on yourself or are you setting your terms of reference to be far too wide?

- Use custom segments and goals to identify whether your digital platforms are working as they should be.